Writing in Public

Political Humour in the Streets

Hello subscribers to Pen in Fist! Apologies if you receive this week’s newsletter twice: still working out technical issues. In the meantime, read on and enjoy!

Some years ago, I interviewed a woman who had participated in the Basque struggle for independence following the death of the Spanish dictator Francisco Franco in 1975. She had been a supporter of armed activism and had spent some time in prison, and had also been involved in the incipient Basque women’s movement. Like almost all the women I interviewed about their activism in those years, this woman’s memories of feminism often focused on the fun times she’d had organising with other women against a backdrop of uncertainty, tension and violence during the years of the Spanish transition to democracy.

One particularly funny memory involved a group of feminists in a working-class neighbourhood in Bilbao covering the walls of their barrio with posters providing instructions to women on how to masturbate. The recollection of the audacity of this action, and of the reactions of bemused neighbours, sent the interviewee into peals of laughter. Even by the time we were talking in the 1990s the campaign seemed a bit absurd. But at the time there had also been something very serious about young women who had been raised under an ultra-Catholic authoritarian regime publicly claiming their right to sexual pleasure.

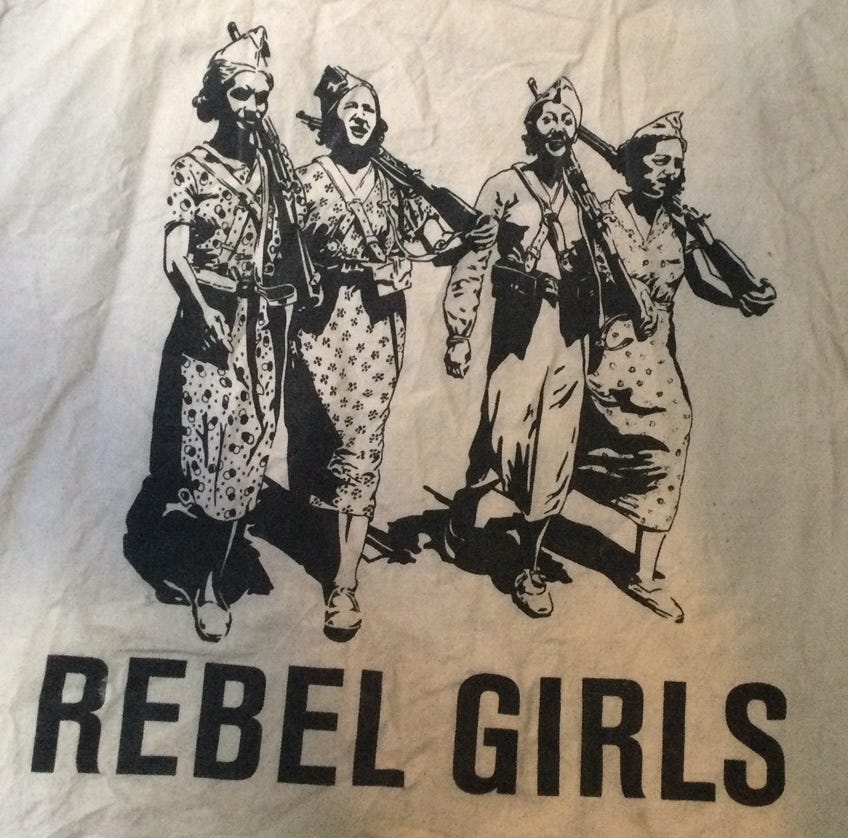

I thought of these youthful Basque feminists and their irreverent do-it-yourself sex-ed classes last week as I marched on International Women’s Day in London’s Leicester Square, surrounded by people carrying defiant and often witty placards and banners. Like generations of feminists before us, who took over their local squares and streets to speak to one another and send messages to a wider public, these feminists were using creativity and wit to alter the language of public urban space.

Playful sayings of protest, often scribbled lovingly in bold felt-tip marker on the backs of cardboard boxes, are a highlight of any demo I go on. This year I detected a theme: a series of sharp statements using humour to celebrate women’s sexual pleasure while talking back to the violence of sexism.

Sex is art and I’m an artist

I’m fucking the patriarchy. Are you?

Blow jobs are real jobs and real jobs suck

Love sex, hate sexism

My favourite position is CEO

Feminism has a funny relationship to humour. The stereotype of feminists as misery guts is like a mouldy roll that gets passed around at a never-ending male chauvinist dinner party. Yet feminism itself is too often taken to be a bit of a joke, a political movement that lacks the urgency of, say, climate change or war (as if there were nothing feminist about these “bigger” issues). Feminism, it seems, is both too serious and not serious enough.

Add to this the fact that there’s nothing particularly funny about rape and sexual harassment, and making a joke of sexism seems a tall order.

In this context, feminist witticisms about sex are small texts that pack a big punch. My favourite position is CEO is more than wordplay: it turns macho humour on its head: “Sexist humour is boring. We’re smarter and we don’t want to do it with you!” Love sex, hate sexism has become a bit of a mainstream feminist slogan. But when it appears on a poster at an International Women’s Day march I also detect a wink at other feminists: Sex is not a biological fact to be used to divide women. It’s an act––a form of pleasure we claim back in the face of violence.

On a rally, the humour expressed on placards often contrasts with the more direct and serious tones of political speeches. But that doesn’t mean the posters represent some kind of feminism lite or, to paraphrase the late US radical feminist Andrea Dworkin, “fun feminism”. To the contrary: placards use humour to make a serious point about the ongoing problem of sexism. And when they’re out on the streets, feminist words provide a jarring contrast to the banal messages of advertising and consumerism that we cannot escape in the contemporary urban landscape. Not unlike the Basque feminist posters plastered in public spaces that for decades had been monopolised by fascist and religious symbols, today’s feminist posters interrupt the numbing effect of neon letters that try sell feminism back to women in the form of individualised messages like “Because you’re worth it!”

The occasions to read subversive feminist messages feel all the more precious in an age when so much creative work is done online. Feminist memes in many ways reproduce the cleverness of street posters, like those the Guerrilla Girls famously plastered close to New York art galleries in the late 20th and early 21st centuries to denounce the sexism and racism of the mainstream art scene, or the lesbian feminist anticapitalist and antiimperialist graffiti of Bolivian lesbian feminist Mujeres Creando on the streets of La Paz:

Tu me quieres santa. Tu me quieres virgen. Tu me tienes harta. / You want me to be a saint. You want me to be a virgin. What you’re making me is sick.

But memes are most likely to be consumed on private devices and don’t have the same power to transform our physical public space. As paper billboards are replaced by rolling adverts that disappear every few seconds, there fewer opportunities to re-write the sexist language on the streets, like this iconic British example from the late 1970s, captured by photographer Jill Posner:

Image: Jill Posner, 1979; Source: Tumblr

Poster, flyers and other paper documents created by and circulated among political activists – what historians refer to as ephemera – risk getting lost over time; when they survive, they often end up in people’s attics and basements, or in small specialist archives. Yet they are as much a part of political history as the texts preserved in official collections. And they often tell a very different story to those that are based on mainstream sources. In her study of Irish Republican pamphlets from the period Troubles Laura Lyons writes about a Sinn Fein poster warning of changes to the benefits system brought in by the 1988 Social Fund Act. The flyer has a photo of then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher with the words

WATCH OUT! THERE’S A THIEF ABOUT… DON’T BE MAGGIE’S APRIL FOOL – CLAIM NOW!

As Lyons says, the flyer’s use of parody chimes with popular Irish culture and “highlights the wit and playfulness within republicanism”. This history of using humour to make serious political points risks being lost in the sea of British media “caricatures of the IRA and its supporters as a gang of brutish thugs”.

Placards, graffiti and flyers are some of the best examples of radical political humour. They’re worth holding onto not just for the cathartic force of laughter the provoke but because they have the power to change the stories we write about political movements and activist histories. And who knows? After the apocalypse they may be all that remains––like the comic book in Station Eleven that survives to tell the tale and shape the future once all the phones and computers shut down for good.

Next week: Let’s write about drugs

Just came from the writer's hour to check. Really nice! Spanish women have an especial appreciation of feminism that is quite cool.

Love this! Looking forward to the next issue!